This post was a collaborative effort by the eBird Northwest Team, of which Pacific Birds is a member. Thanks to Julie Hagelin, Alaska Department of Fish and Game, for adding more to the story.

A Flycatcher in a Dangerous Decline

Olive-sided Flycatchers may not be well known to casual birders, but they have certainly made news among ornithologists and conservationists. The species has been in a consistent decline for decades and people are trying hard to find out why.

This neotropical migrant is almost exclusively a Western Hemisphere bird that is generally associated with forests. It has a distinctive song (Quick, Three Beers or Quick, Three Cheers, depending on the audience) and is distinguished from other flycatchers by the tuxedo-like pattern on its breast.

Habits and Habitats

As an aerial insectivore, or a bird that catches insects on the wing, Olive-sided Flycatchers often perch in a tall snag or live tree where they forage for prey. They may consume their insect food while airborne, or return to their perch to finish it off. During the breeding season, males advertise their presence from these same tall trees. This species stands out among North American songbirds in being obligate aerial insectivores and having one of the longest annual migrations.

On the breeding grounds, Olive-sided Flycatchers are associated with coniferous forests and water, generally in more open forests or forest edges. Because they prefer those open areas – think swooping down from a snag to catch food – they are also frequently associated with burned or logged environments. During migration, their habitat preferences widen and on the wintering grounds they are found mostly in montane forests, where they still seek out the tallest trees in the forest.

While Olive-sided Flycatchers are associated with burned forests, what drives their success – or lack of – in those areas is not fully understood. It seems to be more than just if there was a fire, but how intense it was.

In 2015, researchers published results from a 10-year study on the effects of an Oregon fire on forests and bird communities. A key finding of the study was that for some species, fire intensity was a key factor to whether or not the birds benefitted. In the case of Olive-sided Flycatchers, there was an initial decline where the fire intensity was greater, but that was followed by an upswing due to regrowth of an insect-laden shrub understory and standing dead trees for perching and nesting. The response of birds to fire intensity varied by species, however, showing the value of mixed-severity wildfires to bird communities overall.

The Olive-sided Flycatcher, a Watch List species, is one of the most at-risk western forest birds. The direct cause of population declines remains a mystery that is complicated by the birds long-distance migration.

Our results show that Olive-sided Flycatchers prefer the most severely burned patches after a mixed-severity wildfire. This knowledge can lead to improved forest management in fire-adapted ecosystems.

- John Alexander, Klamath Bird Observatory

Range and Migration

More than half of Olive-sided Flycatchers breed in the boreal forests of Alaska and Canada. Their breeding range also includes coniferous forests of the western U.S., and the northern Midwest and eastern states. Their wintering range is concentrated in the mid-elevations of the Andes in western South America, though they also overwinter in Central America and even the lowlands of the Amazon.

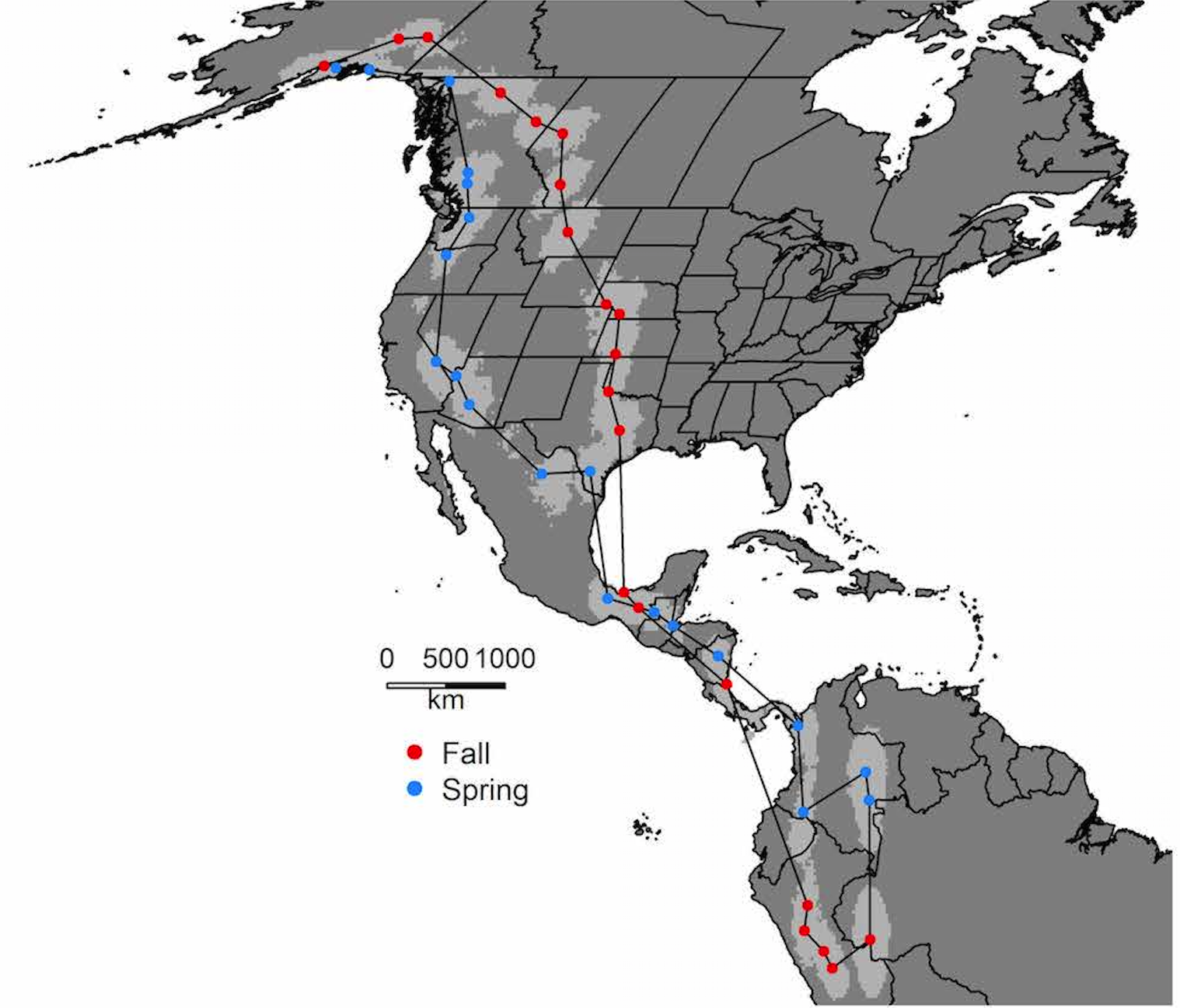

A 2013-2016 study by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Migratory Bird Management, and the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute Migratory Bird Center used geolocators, a small lightweight device used to help track birds, to learn more about the migration route and wintering areas of birds breeding in central and southcentral Alaska.

Photo - Julie Hagelin

When the tagged Alaska birds returned in spring, the data showed their fall and spring migration routes, how much time they spent at points along the way, and their overwintering locations. Individuals wintered in Ecuador, Peru, Brazil and Colombia! Some stops throughout the journey (in the Pacific Northwest, Mexico and Central America) were important to a reasonable proportion of the tagged birds, indicating these could be important locations to maintaining habitat connectivity for Alaska breeders.

In total, Alaska breeders averaged a remarkable annual journey of roughly 12,000-14,000 miles—the entire distance powered by insects!

- Julie Hagelin, Alaska Department of Fish and Game

THE ANNUAL JOURNEY OF AN ALASKA BREEDING OLIVE-SIDED FLYCATCHER

Map courtesy of Julie Hagelin

Population Trends and Conservation Status

As a group, aerial insectivores are experiencing sharp population declines and the Olive-sided Flycatcher is no exception. Data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey shows a cumulative decline of about 80% over the past 50 years. The species is listed on the Partners in Flight Watch List as a species of the highest conservation concern.

What is driving this population decline? Habitat loss on the wintering grounds, such as extensive deforestation in the Andes, is one suspected cause. Forest management practices and habitat alterations on the migration or breeding grounds could also be affecting the population. And, as been noted with other insectivores, the species could be suffering from a global decline in insect populations, as well as climate change driven shifts in when their prey hatches which affects the food available to chicks.

Next Steps

Research into Olive-sided Flycatchers is continuing, with new technologies that will further pinpoint where birds spend their time over the course of the year. This specificity of individual birds’ locations over their annual cycle could help fill in the puzzle pieces about the precipitous population declines and help target future conservation actions.