This post was submitted by David Bradley, Bird Studies Canada. Dr. Bradley is a member of the Pacific Birds International Management Board. While this article features Haida Gwaii, the harm to island birds from invasive species is an all too familiar story across the Pacific Birds region and the world.

Biosecurity is key to preventing extinctions

Islands throughout the world’s oceans contain biologically diverse ecosystems due to their isolation and remoteness. These islands also harbour organisms that have evolved without the influence of genetic mixing from mainland populations, a characteristic that lends itself to both uniqueness and susceptibility. Unfortunately, when humans get to these islands they often transport plant and animal species that are not naturally endemic to the island, known as Invasive Alien Species (IAS), which can wreak havoc on the indigenous flora and fauna. Invasive Alien Species are now the leading cause of avian extinctions worldwide, and have created a quandary whereby islands have the smallest surface area and yet have the highest extinction rate of any habitat on earth. Invasive alien species have driven more than 50% of bird species extinctions since 1700.

British Columbia, Canada, has many hundreds of offshore islands that host millions of breeding seabirds each year ranging in size from the diminutive Cassin’s Auklet and Fork-tailed Storm Petrel, to the comparatively hefty Common Murre and Glaucous-winged Gull. These birds are able to reach large population sizes due to the protection that isolation has provided in the past. However, recently the impact of IAS such as rats, raccoons and mink have begun to impact the numbers of seabirds that once flourished on BC’s coast. Fortunately, IAS can be dealt with through diligent and well-planned measures involving three biosecurity pillars: detection, eradication/control, and prevention.

A good example of the eradication pillar of biosecurity occurred in 1995, when the Canadian Wildlife Service removed rats from Langara Island off the northern tip of the Haida Gwaii archipelago. Langara Island once contained one of the largest seabird colonies on the Pacific Coast of Canada, before Black Rats were introduced early in the 20th century. Once established, these invasive mammals were able to rapidly increase in numbers and cause a remarkable impact on all of the seabirds breeding there.

Most notable of the seabird victims was the Ancient Murrelet, which were reduced from several hundred thousand historically to fewer that twenty thousand by 1993. Once poisoned bait stations were established on-island, the numbers of rats dropped dramatically. The rats have not been seen on Langara Island since, despite intensive detection monitoring using remote cameras set up by Bird Studies Canada. The good news is that Ancient Murrelet numbers are now rebounding.

Long-term Success will take Prevention and Partnerships

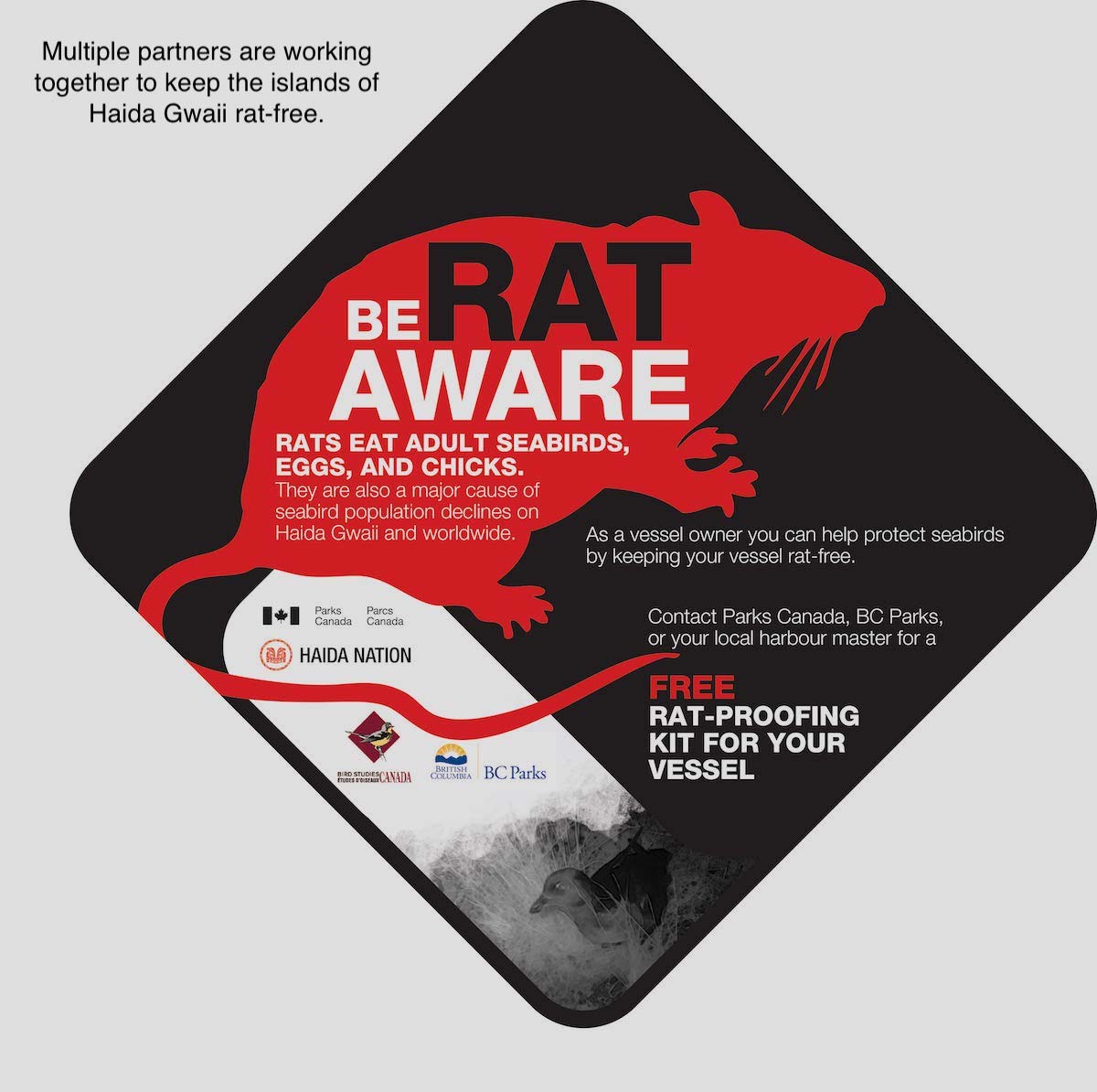

The short term success of island-wide eradications, such as the one that occurred on Langara Island, can only be maintained in the long-term by implementing the 3rd biosecurity pillar; prevention. Bird Studies Canada has worked with local and federal governments, and local indigenous partners at the Council of the Haida Nation to establish a rat awareness campaign aimed at boaters to rid their vessels of invasive mammals. They have also put on local events to increase popular support for biosecurity measures, and provided scat and paw print identification pamphlets to groups that visit some of the islands. This long-term support is crucial to ensuring that invasive mammals have a limited future impact on Haida Gwaii's seabirds. Future work to reduce the impact of IAS in British Columbia will require significant funding and partnerships.