Thank you to Krista De Groot for submitting this post. Krista is a biologist with Environment and Climate Change Canada and was the lead author on the paper mentioned below.

Artwork created by Derek Tan (Biodiversity Research Centre, UBC).

Photo: K. De Groot

A coastal British Columbia research study reveals high collision mortality throughout the non-breeding period.

As the world becomes increasingly urbanized, population declines due to habitat loss and degradation may be compounded by a range of additional threats that cause direct mortality to birds. Glass is one such threat–it is responsible for the deaths of an estimated 16 to 42 million birds per year in Canada and up to almost a billion (365 – 988 million) birds in the U.S. alone. While songbirds are the most common casualties, collisions with glass affect a range of other taxa including ducks, grouse, eagles, hawks and owls.

Glass surfaces on buildings pose a significant hazard to birds since glass is both reflective and transparent. Reflections in glass create mirror images of the natural environment, and birds mistake these visual extensions of sky or vegetation for the real thing. Transparent glass, often found in two sides of a lobby, or in glass railing systems and glass overpasses, creates an invisible barrier in the middle of flight paths and between habitat patches.

Photo: A. Huang

Collision rates are typically highest during the migratory periods, when large numbers of birds stop to rest and refuel in cities. It is not just a problem during migration season however, as the heavily developed low elevation areas of the Pacific coast from British Columbia to California also host high densities of terrestrial birds during winter such as thrushes, sparrows, and finches.

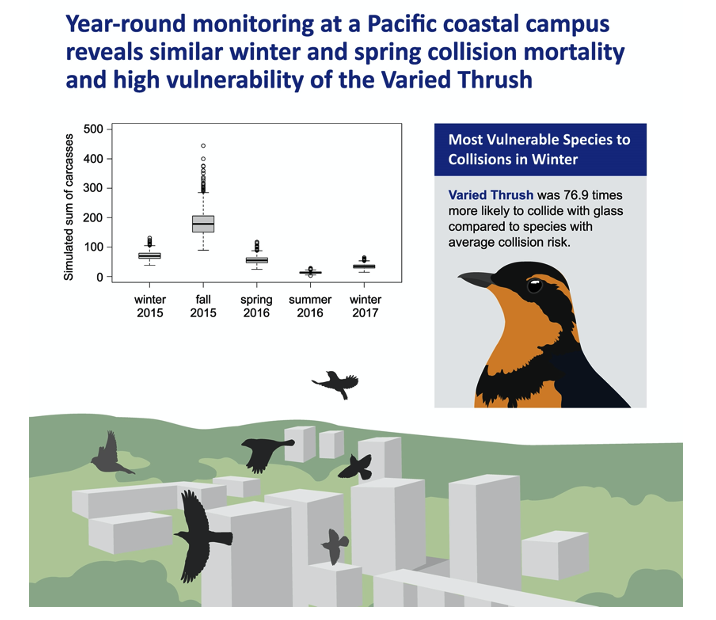

A recent study conducted by Environment and Climate Change Canada at the University of British Columbia, Year-round monitoring at a Pacific coastal campus reveals similar winter and spring collision mortality and high vulnerability of the Varied Thrush, found that collision mortality rates are high throughout the non-breeding period which includes fall migration, winter, and spring migration. This represents an extended period over which collision mortalities may accumulate along the Pacific coast compared to other areas in North America.

Potential implications for Pacific coastal birds

While much of the previous research on this topic has been conducted in eastern and central U.S., this study indicates that winter collision mortality may be an overlooked conservation issue in western coastal urban areas. If winter mortality is high in urban cities of the Pacific Northwest, the cumulative impacts to both migratory and resident species could be more significant than realized. The research identified several species that were particularly vulnerable to collisions in winter 2017, including two species that only breed in Western North America. Varied Thrush (Ixoreus naevius), and the Spotted Towhee (Pipilo maculatus) had the highest relative collision vulnerability of the 26 species with recorded glass strikes, even when species abundance was accounted for. This suggests that some species could have intrinsic vulnerability to collisions, perhaps related to their behavior or foraging habits.

Take Action

There are effective solutions to the bird strike problem. The most important action is to make glass visible to birds from a sufficient distance that they are able to recognize the barrier and avoid it. The American Bird Conservancy (Glass Collisions: Preventing Bird Window Strikes) and FLAP Canada provide comprehensive resources for reducing this conservation threat. Art work designed with bird-friendly criteria in mind and applied to glass can be not only a beautiful solution, but one that tells a story about the building or its surroundings.

Pacific Birds habitat conservation partners can help ensure that structures on conservation properties are designed or retrofitted to reduce bird deaths caused by collisions. Let’s all do our part to ensure our homes, workplaces and communities are safe for birds.