Bob Wick, Bureau of Land Management

Severe drought and water shortages in parts of the Pacific Northwest–and across the West in general–have the potential to impact Pacific Flyway waterfowl. We sat down with Dr. Mark Petrie to learn more about the impacts of drought on Pacific Flyway species. Mark has spent many years working to better understand and conserve waterfowl populations. He is currently the Conservation Planning Director for the Ducks Unlimited Western office and is the Waterbird Science Liaison for Pacific Birds.

It is estimated that more than a billion birds use the Pacific Americas Flyway, many of them ducks and geese that breed in Canada, Alaska and the northern contiguous U.S. states. While the entire flyway network of wetlands, bays, estuaries, agricultural fields and other habitats are important, three regions are especially valuable to the Flyway’s waterfowl–the Central Valley, the Klamath Basin, and the Great Salt Lake.

Seventy percent of waterfowl in the Pacific Flyway use these three areas from early September to late April, and the habitat conditions in those places can impacts birds across the Flyway. One thing that has been happening in recent years in those three locations, and across much of the western U.S., is moderate to extreme drought. Since the mid-1950s, the snowpack in the mountains–the main source for water in the lowlands–has been diminishing, and the spring melt has come earlier, leading to more evaporation and ultimately less water where and when waterfowl need it. The lack of water for sustaining bird habitats has caught the attention of Ducks Unlimited, Joint Ventures, Refuge managers, and many others in the bird conservation community.

In California’s Central Valley, the snowpack, rice fields, waterfowl populations and waterfowl hunting are all inextricably linked. In non-drought conditions, more than 500,000 acres of rice are typically planted, and in 2022 only about 260,000 were planted. That rice provides about half of the food for Pacific Flyway migrating and wintering waterfowl, and the winter flooding of rice fields provides important shallow water habitat. The impacts of less water are felt keenly–not only by rice farmers but to hunters and other bird enthusiasts. The drought does not necessarily lead to a decline for flyway waterfowl populations in the long term, however. As Mark explained, droughts have hit the Central Valley, and other western locations, before without lasting consequences to bird populations. Scientists don’t have a full picture of where birds go in response to drought, however, or whether this current drought is a harbinger of a drier future climate.

Like the Central Valley, the SONEC region–Southern Oregon and Northeastern California–is currently in and extreme drought. This a region of working agricultural and grazing lands and is also home to the six Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuges. Before European settlement the Klamath Basin was comprised of freshwater wetlands and lakes that supported millions of Pacific Flyway birds. Irrigation, flooding and other water management tools have been used to try to balance the current multiple needs for water in the Klamath Basin, but that–as is true elsewhere–requires adequate snowpack in the surrounding watersheds. Without adequate surface water, wintering birds–such as Mallard or Green-winged Teal–may not be as healthy on their journey to their northerly breeding grounds and they are more prone to disease as birds crowd into remaining wet areas. Waterfowl hunting is also impacted; in 2022, several areas in the Basin are closed due to bone dry conditions.

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

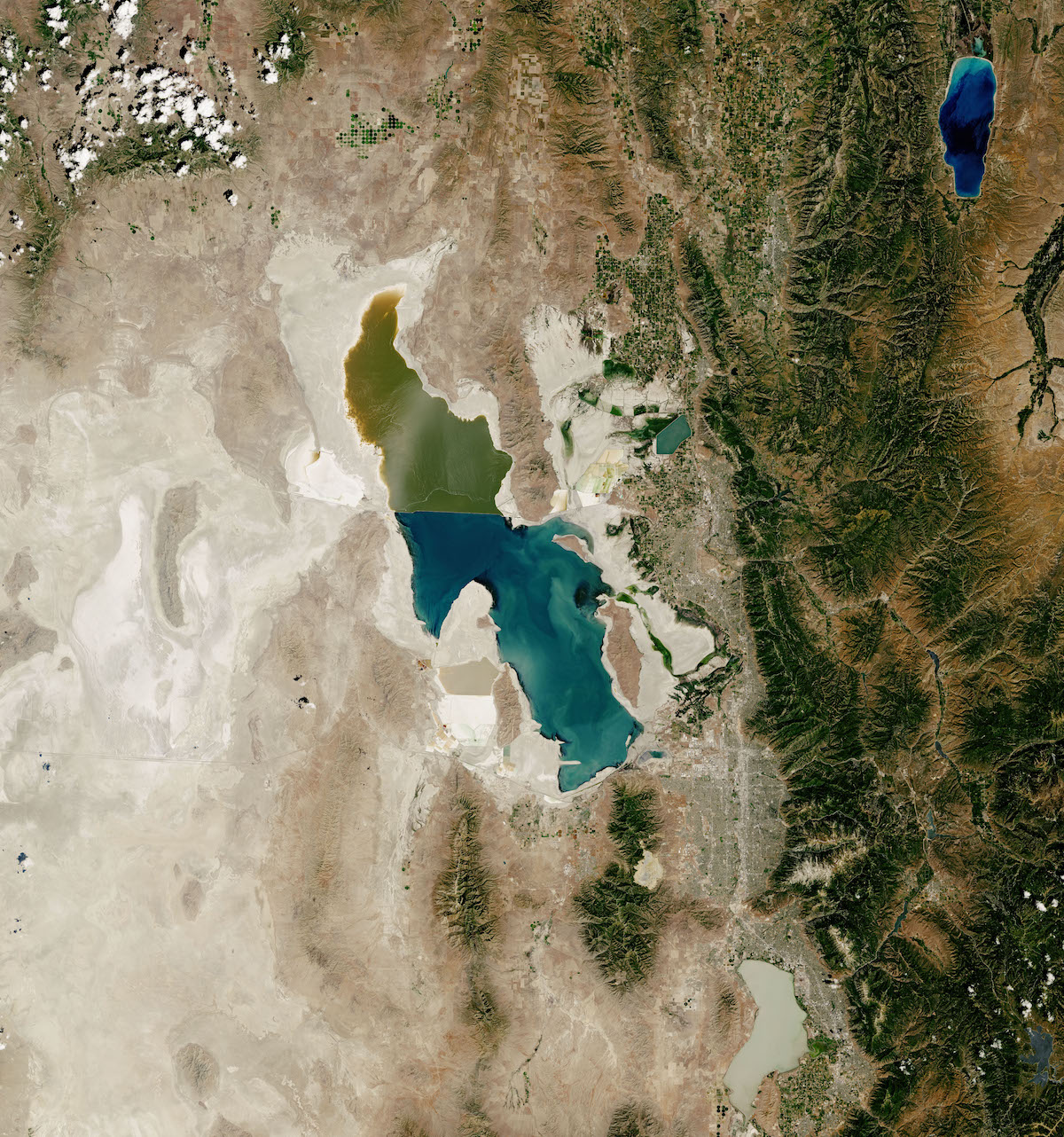

Great Salt Lake, at the eastern edge of the Flyway, is a mecca for not only waterfowl but shorebirds. Continuing the recent trend in water levels, the lake could lose two feet of elevation in 2022, resulting in saltier conditions and fewer brine shrimp, a key food source for migrating birds. Associated freshwater wetlands are also impacted, creating an even greater challenge for birds looking to rest and refuel.

So how do managers, conservationists, landowners, hunters and others with an interest in the Pacific Flyway’s birds help solve this quandary of ensuring that waterfowl and other birds have adequate habitat, given that the snowpack is simply not there? As Mark explained, there are no easy answers. Two things stand out, however: we need to come together to find local solutions related to water management, and we need to learn all we can about what birds are doing in response to drought so we can plan for conservation. In the Klamath, for example, Ducks Unlimited is working with a variety of conservation partners to help evaluate the impacts of the drought using aerial surveys and fitting ducks and geese with satellite transmitters. Similar collaborations, including many Joint Venture partners, are working in other areas to help birds make it through the dry years. As Mark put it, it is an opportune time to band together for birds!

NASA Earth Observatory