Andy Reago & Chrissy McClarren © Creative Commons

While millions of birds are winging their way north via the Pacific Americas Flyway, we take a look at a shorebird that uses at least one additional flyway, traveling the vast Pacific to reach northern breeding areas.

This post was submitted by Lynn Fuller, Pacific Birds Communications Coordinator, who happens to love Tattlers.

Wandering Tattlers (Tringa incana) easily capture the imagination–they do, really, wander the Pacific and there are many unknowns about them in the literature. There are many common names for this species. In Hawaiian, they are known as ʻŪlili and in Tahitian, Uriri – both more onomatopoetic than tattler which likely refers to its behavior when alarmed. People of the Cook Islands have various names for this bird, among them Kolili and Kuriri. The birds are found within several indigenous language areas in Canada, Alaska and Siberia.

The most recent Tattler I saw was along a rocky and muddy cove in Alaska’s Kachemak Bay. It stood out even from a distance–it was too chunky for a Yellowlegs, it was solitary and it made its classic alarm call when I moved closer for a better look. It was the second week of May, so I didn’t know if this was a migrant stopping over to refuel or if it would be nesting more locally. Either way, the bird’s journey and behavior intrigued me.

Distribution and Migration

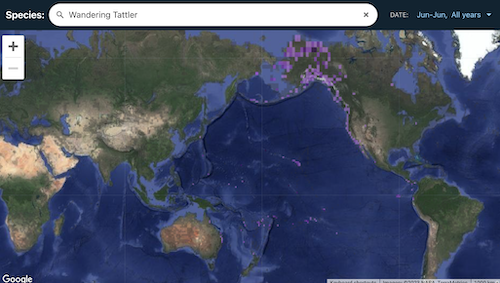

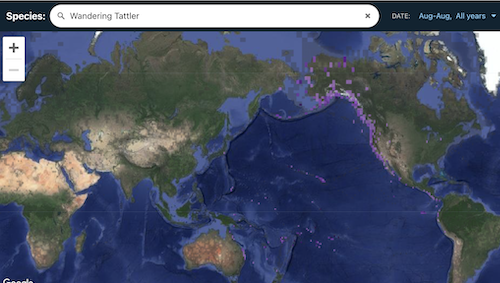

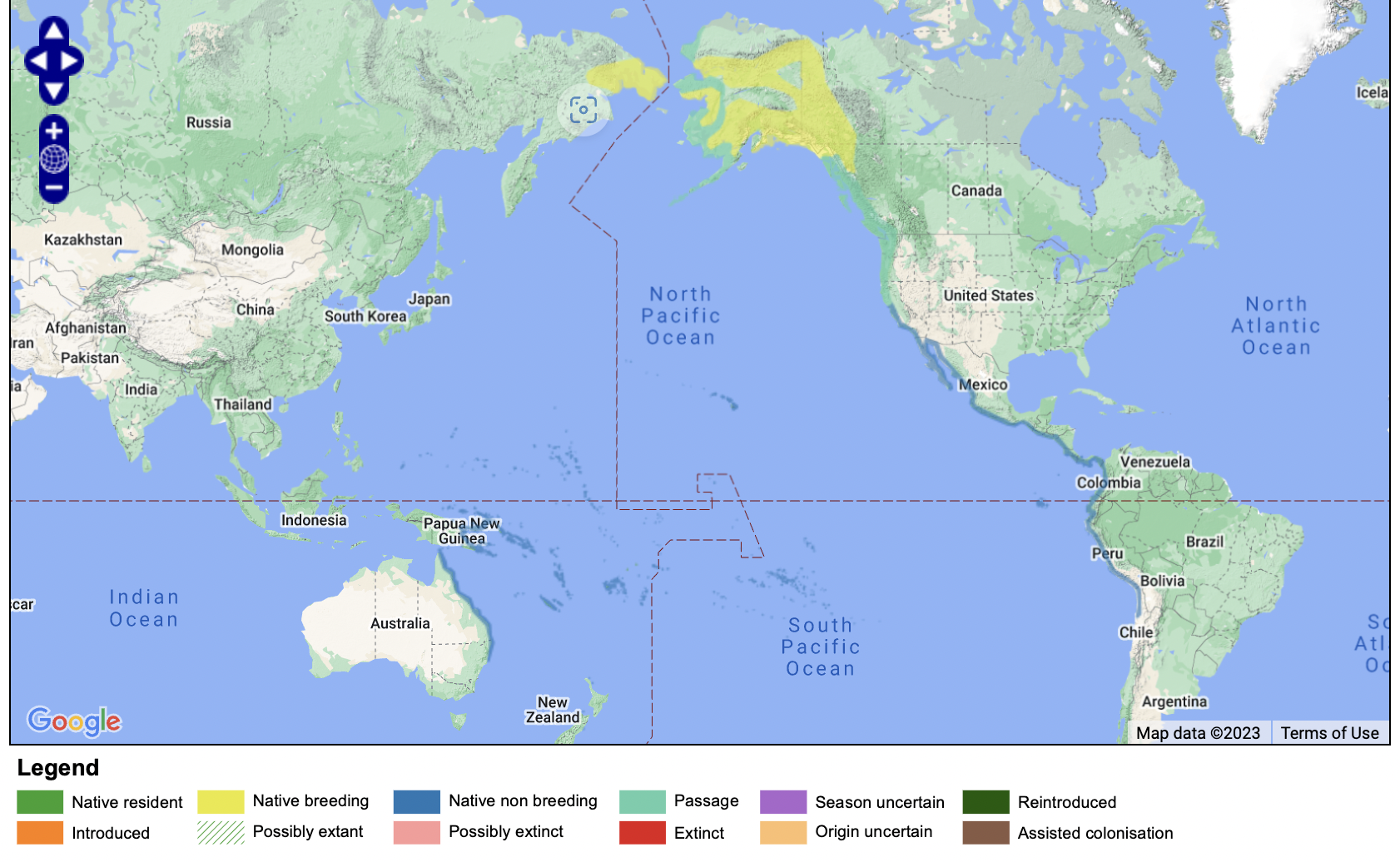

Wandering Tattlers have a broad distribution surrounding the Pacific Basin. They spend the Northern Hemisphere summer in Alaska, far western Canada and northeast Russia, usually arriving on the breeding grounds in May to early June and departing for the nonbreeding grounds starting as early as mid-July. The bulk of the migrants are believed to travel via the Central Pacific Flyway to wintering areas in Oceania (including the Hawaiian Islands) and East Asia-Australasia, but some of the population overwinters along the Pacific Americas.

Studies done in the late 1990s showed an Alaska-Hawaiʻi migratory connection, when two birds marked at Turquoise Lake in southcentral Alaska were later resighted in Hawaiʻi. Like the Pacific Golden Plover, some of the Tattlers make Hawaiʻi their winter destination, while others spend the nonbreeding season further south. This project in Alaska, described in Breeding ecology of Wandering Tattlers Tringa incana : a study from south-central Alaska, was the first time that marked birds had been resighted on the nonbreeding grounds. While these resighted birds confirmed the birds’ 4500 km migration from Alaska to Hawaiʻi, there is still more to learn about the longer flights to nonbreeding habitats in southern Oceania. Birds that winter in California and further south seem to migrate through Oregon, Washington and British Columbia, but the timing and routes from there needs more study.

Map from Bird LIfe International

Habits and Habitats

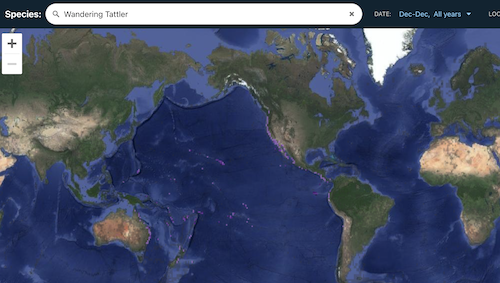

Tattlers are tail-bobbers much like the smaller Spotted and Solitary Sandpipers, and they are often solitary or in small groups. The habitats they frequent varies with geography and time of year. During migration and the breeding season, they are often seen seeking invertebrates or small fish along rocky coastlines, mudflats, lakes and streams. In the nonbreeding season, they also spend time on the ubiquitous beaches and other habitats of Oceania and Asia, as well as a suite of habitats along the North and South American coast. Throughout their nonbreeding range, they may also be seen in developed areas such as near resorts, piers, and airports.

Tattlers generally nest in montane habitats that have proximity to water, though lower elevation nests have also been recorded. Depending on the location, birds arrive on the breeding grounds in May and June. The nest usually contains four eggs, incubated by both males and females, and eggs hatch in late June to early July. Starting in July, the adult birds leave the breeding grounds, followed by immature birds. Young birds may stay on the nonbreeding grounds for up to three years before first migrating north, explaining why they might be observed on their nonbreeding range year-round.

Population and Conservation Status

The Partners in Flight Conservation Assessment Database puts the total global Wandering Tattler population at 18,000 birds, which falls within other global estimates of 10,000-25,000 individuals. Based on Breeding Bird Surveys and Christmas Bird Count data, there has been a significant decrease in population over the past 40 years, prompting the bird’s inclusion on the State of the Birds 2022 Tipping Point Species list and its inclusion on the Road to Recovery list.

Most ranking systems have an elevated level of priority or concern for the Tattler. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Birds of Conservation Concern 2021 list includes Wandering Tattler as a species of concern at the continental level, and as a nonbreeding species of concern in the Hawaiian and other Pacific Islands. It is listed as a priority species for conservation or stewardship, depending on the Bird Conservation Region, by the Government of Canada. It is a Species of Greatest Conservation Need in the Alaska State Wildlife Action Plan, and listed as a climate vulnerable species in the California Plan. It is a high priority species in most of its range in the Alaska Shorebird Conservation Plan.

Because of the solitary and often remote habitat preferences of this species, global population numbers and trends are hard to pin down, but the observed declines in data we do have is of concern. As with other shorebirds, climate change leading to sea level rise and vegetation changes, non-native predators, and habitat loss are potential drivers of population declines.

Where are Wandering Tattlers Now?

The northward migration has already started for some of the Tattlers, depending on the nonbreeding location. Cumulative, global eBird sightings show where they have been recorded for any selected time period (March, June, August and December shown below). With vast migratory flights over the vast Pacific for some of the birds, and the often remote, roadless breeding and nonbreeding locations, there is still a lot to fill in about where these birds are over the course of the year, the journeys they take and their behavior. For our partners and friends in the Hawaiian Islands, Alaska, Canada and the Pacific Northwest–keep a look out!

LEARN MORE FROM ACROSS THE PACIFIC

See Birds of the World for a comprehensive discussion of what is known about Wandering Tattlers.

BirdLife International (2023) Species factsheet: Tringa incana

Alaska Species Ranking System–Wandering Tattler

Breeding ecology of Wandering Tattlers Tringa incana : a study from south-central Alaska

Read a southern hemisphere perspective, from the Tetiaroa Society.

From the American Birding Association: How to Know the Birds: No. 21, Hawaii’s Most Perfect Bird

Wandering Tattler in Hawaiʻi, from the State Wildlife Action Plan