We recently had the privilege of speaking with Dr. Andrew Stillman of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. He is part of the eBird team there, where he and the rest of the team make sure eBird data can be applied to research projects around the globe. eBird, a citizen science birding platform, has taken the world by storm since its launch in 2002, with over 100 million bird sightings contributed annually by eBirders and a 20% annual growth rate each year.

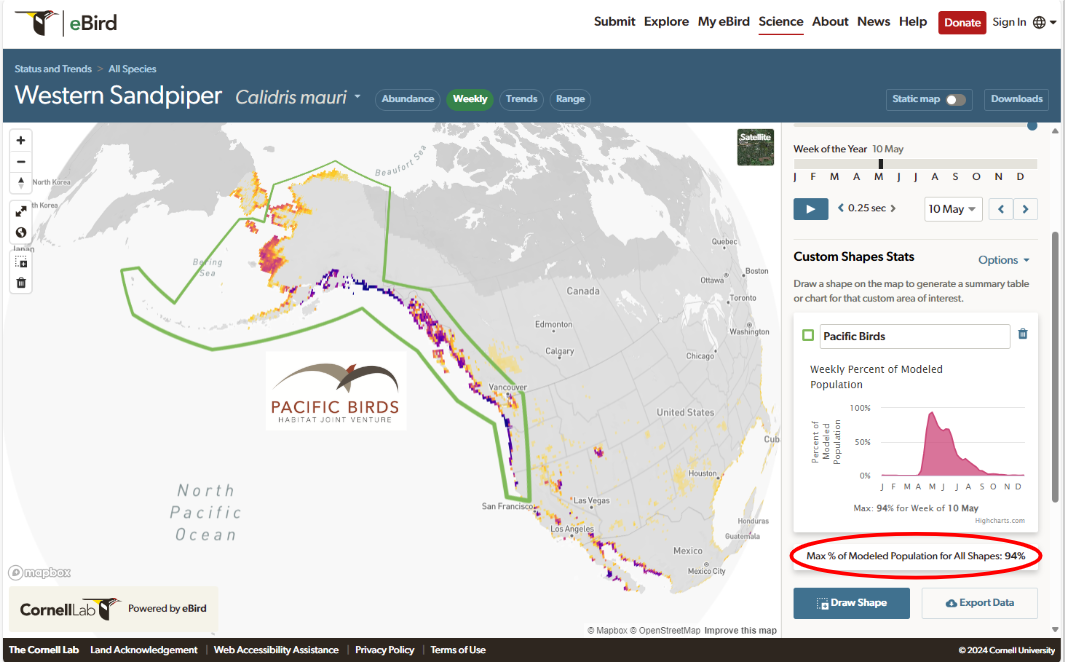

In 2022, eBird connected with Migratory Bird Joint Venture staff at Pacific Birds and six other Joint Ventures (JVs) working from Canada to Mexico. Together, eBird and JV staff are working to answer pressing conservation questions, like: How many and which bird species occur within each JV region across their annual life cycle? What time of year do specific birds or bird groups migrate through a JV region, and where are important hotspots for multiple species?

With a thriving workgroup established and a new publication under review to share real-world applications of eBird data products with the broader scientific community, the collaboration has been a success and will continue to grow. We connected with Dr. Stillman to discuss why this project is important to eBird’s goals and how the partnership has impacted his work.

*This interview transcript has been edited for clarity and length

Natalie: I’d love to hear about your role with Cornell and how long you've been there to start.

Dr. Andrew Stillman: I'm an applied quantitative ecologist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. I've been working with the eBird team since 2021, and my job is to do some of the quantitative heavy lifting to make big datasets, like eBird, as useful as possible for conservation.

Much of my work focuses on conservation efforts in the United States. For example, some of my projects leverage eBird data to understand relationships between birds and their habitat, birds and wildfire impacts, and more. And then other projects involve taking data products and summarizing them in ways that make them more available and easy to apply.

Natalie: What led to this collaboration with JVs?

Andrew: It started just after I joined Cornell. My supervisor, Viviana Ruiz Gutierrez, had been working with several different state agencies. I came on and started answering some of their analysis requests, and it was stuff like, ‘we need to know the percentage of population for raptors in West Virginia in the winter’, or ‘we need to know the percentage of population of waterbirds in Florida in the summer.’

We ended up getting flooded with these requests. We realized it was no longer efficient for me to be crunching numbers and analyzing these things on request.

So we produced a website where a group of Cornell students and I took all of these different state-level metrics and maps – the same things we've now produced with JVs – and just ran it through for every single species and every single state. It’s now on a website, easier to work with, and free to download.

From there, JVs were the natural next partner. Talking to people like Laura Farwell and Monica Iglecia, we realized how valuable this information could be for JVs. We could apply some of these same workflows to the JV geographies to make this information more easily accessible.

Talking to people like Laura Farwell and Monica Iglecia, we realized how valuable this [eBird] information could be for JVs. We could apply some of these same workflows to the JV geographies to make this information more easily accessible.

Natalie: That’s great because JV geographies are more aligned with ecoregions than states, so you can't apply a state-specific estimate. How many JVs are involved now?

Andrew: Right. And around 12.

Natalie: Wow.

Andrew: Yeah. It’s Dr. Laura Farwell's leadership that I think made this thing blossom with the JVs. When we were only working with state agencies, we would communicate about the availability of the data through webinars to state wildlife action plan coordinators and other things like that. But they were kind of one-off things, and it was Laura who said, we've got a lot of people that are using this, and they have lots of questions. They want to make sure that they're using it correctly.

And at eBird, we want an opportunity for feedback, including on what we can do differently on our side to make things more useful. For example, we’ve revamped and expanded our online analysis tutorials specifically based on the feedback and needs of JVs.

Now, we are getting feedback from JV staff and partners, who are asking, ‘Am I doing this right? Is this application sound?’ And that led to a monthly meeting that's been productive and fun. It's an incredible group. They're all supportive, and we just try to help each other. It’s Laura’s leadership that made it all possible.

Natalie: Yeah, I think I went to one of those first webinars, with the JVs just going over the data. It was really interesting to see that people wanted to be able to use the tools and get involved with the data, even if that's not where their background lies. Do you have a vision for how this project might evolve? Or are there next steps already planned?

Andrew: That's a great question. My vision is to remain flexible so we can continue to fill needs as they arise. That's where I see my position here: to hear the needs from people like Laura and others at JVs and work together to see if we can leverage this rich information source to positively impact conservation.

In the short term, we've produced a lot of useful information together, but it’s all just sitting on a shared drive online. We'd like to make a nice website so that it's easier to access, easier to scroll through, and find your JV’s information.

And because eBird information is updated regularly, there will be new sets of results from the eBird Status and Trends program coming out in the future. So there will be opportunities to update the information as we continue to work together.

The power of this sort of collaboration is in the partnership... this partnership means that I can change and tweak the things that I do to make sure that I'm meeting physical information needs for organizations that do real conservation work. That gives me a huge joy of being able to influence conservation in a way that I wouldn't get to do if I were just doing things on my own.

Natalie: Outside of wanting to make sure that this data can be useful to governments, to state agencies, and JV's, what other reasons do you think this is an important project?

Andrew: One thing that makes me excited about this particular project and this partnership is, first and foremost, just how great you all are to work with. Everyone that I've met from a Joint Venture is a super motivated, passionate conservation biologist who is devoting their career to making a positive impact.

The second thing that makes me excited about this is that Joint Ventures are trailblazers.

They're the trailblazers who are figuring out the most effective and useful ways to make use of the rich information sources we have from Status and Trends. And in doing so, they provide a model that I think other conservation organizations and conservation agencies can follow. And that's one reason why I think the publication [that we are working on] is so important, because it outlines what that model is and shows how transferable it is to other information needs.

Because the truth is, when it comes to these sorts of questions about prioritizing species, or landscape-scale multi-species inference, things like that - everybody needs the same information that's lacking right now.

We know how to go to the field and collect good data. We know how to monitor bird populations across smaller scales, but this larger scale stuff is really hard to come by, and given that we all have these shared information needs, the JVs are doing a really good job of showing how the data can be applied to their geographies in a way that can be transferred to other conservation groups.

Natalie: I love that. I think so much of it is stuff that everybody says, Oh, it would be great if we had this info. So it makes sense.

Andrew: Yeah. I feel like JVs are acting as an example of how we can leverage information from participatory science for more efficient conservation decisions. And that's increasingly important right now.

Joint Ventures are trailblazers. They're the trailblazers who are figuring out the most effective and useful ways to make use of the rich information sources we have from Status and Trends. And in doing so, they provide a model that I think other conservation organizations and conservation agencies can follow.

Natalie: Do you have ideas for other tools that you might want to work on? Either with eBird, with JV's, or without JV's.

Andrew: Oh, big time. There's a great team of statisticians, birders, and ecologists that work at the Cornell Lab, and we’ve got our eyes set on some exciting future goals.

Something that I'm working on that I'm excited about, and that I think JVs will be a part of, is the ability to begin understanding the relationships between habitat and birds from eBird data. When we see these maps of bird distributions, the information underlying those maps is machine learning associations between habitats, the environment, and birds. We can begin to distill those complex signals to learn how the environment impacts birds and how those impacts change across space.

That's what I'm doing right now with wildfire - understanding relationships between birds and wildfire, and how those relationships change across their ranges. Management actions typically aren’t one-size-fits-all. But we can use some of these modeling approaches to say, OK, now that I have a good sense of the relationship between a habitat variable and a bird’s trend, for example, what happens if I start turning the dials on those models and simulating a change to the landscape? We can then project how that might affect the trends of the birds into the future.

This ability to begin studying the potential impacts of landscape change on birds is an area of future development, and something that I can't wait to work on alongside JVs.

Natalie Myers: I'm sure many JV’s would love to know more of that kind of information, especially because each JV is so different in its focal species, habitats. So that's very exciting to hear.

Andrew Stillman: One other thought that I want to share is that to me, the power of this sort of collaboration is in the partnership. It's in the fact that I can sit here at Cornell University and innovate methods in a nerdy way, but then partner with the people who can see the needs and fill them.

So this partnership means that I can change and tweak the things that I do to make sure that I'm meeting physical information needs for organizations that do real conservation work. That gives me a huge joy of being able to influence conservation in a way that I wouldn't get to do if I were just doing things on my own.

A huge thank you to Dr. Andrew Stillman for speaking with us about his work, the eBird and Joint Venture collaboration, and more. You can learn more about how eBird status and trends data are calculated here, and more about eBird in general here.