Kyle Spragens, Waterfowl Section Manager, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, contributed this post. Thank you Kyle!

Unique Challenges for Conservation

Since the 1990s, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) Waterfowl Section has been particularly interested in the three species of scoters that grace the lagoons, estuaries and near shore wetland habitats of the Pacific Coast from Alaska to Mexico. Surf Scoter (Melanitta perspicillata), White-winged Scoter (Melanitta deglandi) and Black Scoter (Melanitta americana) migrate through and overwinter in the Salish Sea where they depend on the availability of nutrient-rich foods such as clams, mussels, crustaceans and fish eggs to fuel their migration journeys and survive the winter.

While scoters and other marine birds depend upon the Salish Sea habitats, those habitats are difficult to observe or describe. Some areas are hard to visit and therefore may not be well understood or appreciated for their conservation values.

To conserve scoters and other species of interest, we need to address questions such as “How many are there?”, “Where are they and when are they here?”, “What do they need when they are here?” and “Can we influence their populations?” across the species’ annual life cycle. In the realm of waterfowl ecology, conservation and management, we have made impressive strides for species that we can count by aerial surveys in the month of May, or that we find in shallow wetlands, but we have struggled to make similar advances for marine species like sea ducks–which are hard to count during the breeding season, in migration, or during the winter. For example, Surf Scoters nest in remote boreal ponds and lakes making it hard to detect, identify and count them. Their life histories and migration timing and patterns are different from their freshwater waterfowl relatives.

Using aerial surveys to inform management

To help better understand these birds and inform management, WDFW's Waterfowl Section initiated a separate aerial survey with the goal of documenting the annual abundance, distribution and winter population trends of sea ducks and other marine birds and mammals throughout Washington’s waters of the Salish Sea. Since 1994, a complete Washington shoreline transect and a series of off-shore transects that sample different water depths, have been flown by a crew consisting of a pilot, a navigator, and two exceptionally-skilled observers.

Matthew Hamer, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife

Joseph R. Evenson, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife

As a floatplane flies over the water, observers dictate counts of all marine birds and mammals that they see into a recording device that is synced with GPS-locations. This linkage affixes the observers’ verbal accounting to a data-logged point on the water below. This spatially-explicit survey allows analysts and managers to understand more about the environmental characteristics around each observation and to understand differences observed between and within species from year to year. Through these surveys, we now know that more than 190,000 individual birds from 11 sea duck species use the Salish Sea during the winter months.

These winter sea duck counts have led to the Salish Sea’s inclusion in the Sea Duck Joint Venture's Key Habitat Site Atlas. Additionally, the scoters have been adopted by the Puget Sound Partnership as a Vital Sign of Puget Sound health under the Marine Birds Indicator. The winter population status and trends data also serve as the fundamental underpinning of WDFW’s sea duck harvest strategy informing migratory gamebird regulations in the state.

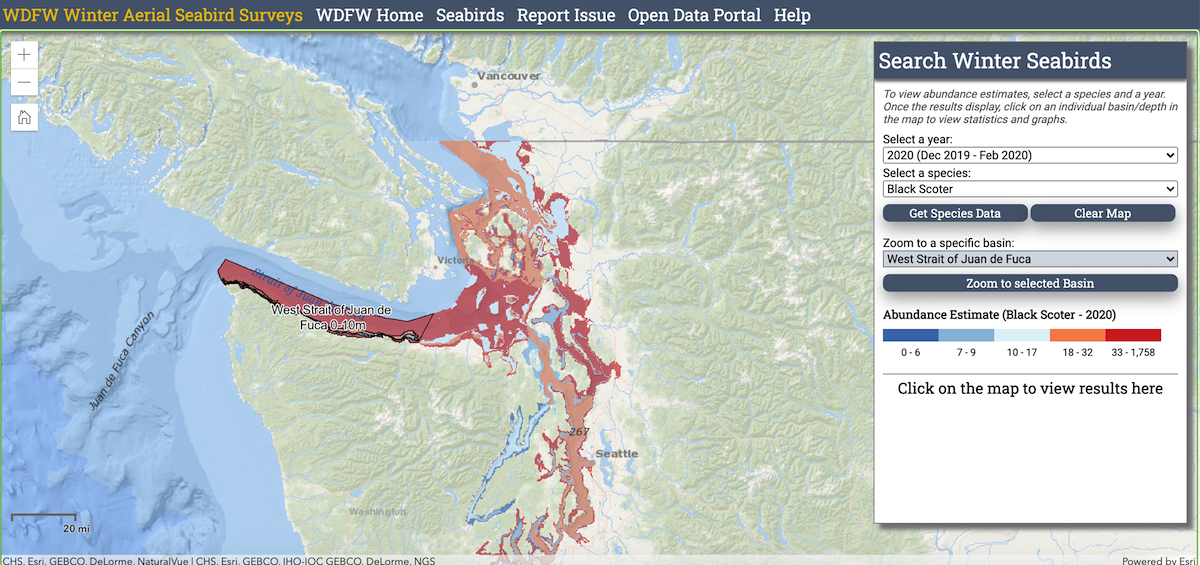

A Tool to Share Seabird Stories

WDFW, with support from the Puget Sound Partnership, recently created an interactive web map based on WDFW’s robust, long-term aerial survey dataset about wintering animal populations. The purpose of the map is to better visualize the abundance and population trends of marine birds and mammals regularly observed in the Salish Sea. You can find information about 40 species, and while WDFW has an interest in all of them, the decline of scoters has been of special concern.

A Story in Plain Sight

While many species of waterfowl are doing well across North America, WDFW survey data show a 40% decline in scoters wintering in the Washington portion of the Salish Sea in the last 25 years. This makes this dataset–and the maps that make the data more accessible–valuable for illustrating a conservation story hidden in plain sight.

For these remotely breeding birds, we suspect the primary causes of the declines may be occurring during the winter season. A recent study from Birds Study Canada showed similar declines in British Columbia’s waters of the Salish Sea, particularly species like scoters that feed from the bottom of the marine waters.

It also reminds us that there is still much to learn, especially about conserving marine habitats important to migratory birds. There is more to this story still to be written. For scoters, knowing what is driving the declines can help us take action to reverse or mitigate them. Researchers, managers, and the sea duck conservation community are gearing up to fill some of the knowledge gaps that remain for Salish Sea scoters. This includes creating habitat association models that will help prioritize areas across the “water-scapes” of the Salish Sea and working with partners in both the U.S. and Canada.

Until then, we have maps that help inform us, and hope we have piqued your curiosity about sea ducks!