Post submitted by Lynn Fuller, Pacific Birds Communications and Outreach Specialist. Thanks to Jeff Fair for sharing his enthusiasm and expertise about loons with me.

A different perspective on spring migration

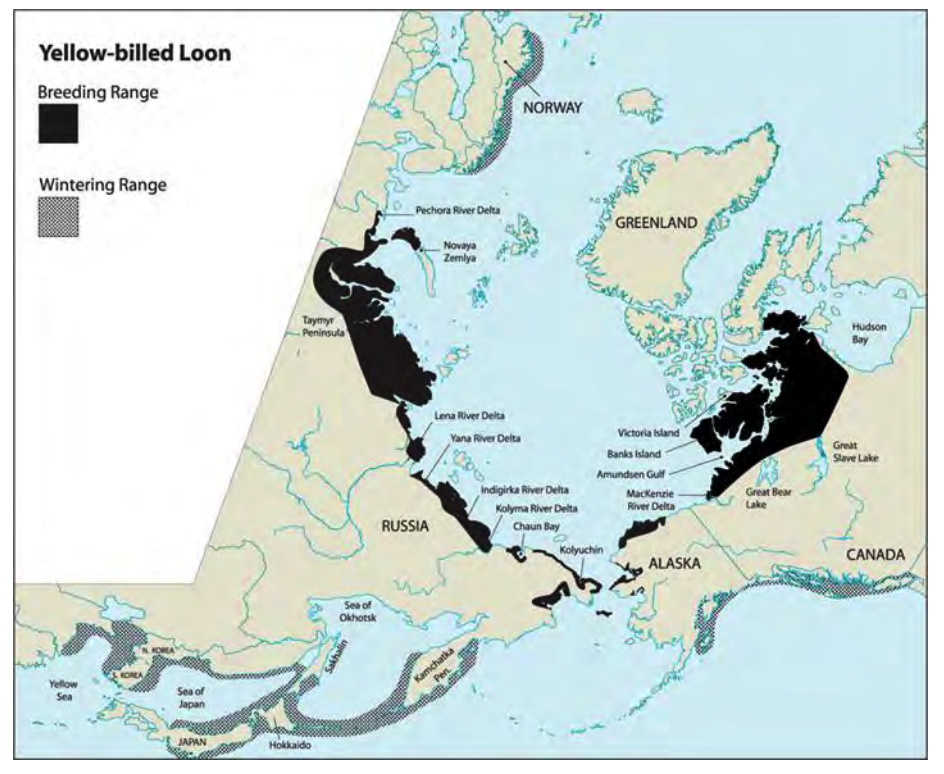

I have never seen a Yellow-billed Loon in full breeding plumage, which isn't surprising when you consider the range map below. Living in southcentral Alaska, and seeing other species of loons with some frequency, the Yellow-billed Loon piqued my interest. Ten years ago they were a candidate species for listing under the Endangered Species Act; they were subsequently removed from that list in 2014 but may come under consideration again. They are a Red-list species on Audubon Alaska's 2017 WatchList.

Regardless of their official status, they are a bird of conservation concern due to their low numbers worldwide and the threats or potential threats across their range. Their numbers are hard to gauge given they are unstudied in large portions of their range but estimates suggest 16,000-24,000 individuals worldwide. Yellow-billed Loons present a lot of unknowns, which makes me want to find out more.

To find out more, I looked at Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Birds of North America (BNA), and I went to the Yellow-billed Loon page on eBird to look at where they have been seen in 2019. I realized how little I knew about these loons, particularly their migration patterns. Even though I remembered that at least some Yellow-billed Loons spend the winter in East Asia, I quickly learned the full extent of my Pacific Flyway and North American bias – I assumed birds that wintered in the coastal Pacific Northwest of the U.S. and Canada would be migrating along or near the coast of southern Alaska and at some point turn north to Alaska’s North Slope to reach their breeding areas. When you look at BNA – or other range maps that are limited to North America – you simply don’t get the complete picture.

I needed a different perspective. I met with Jeff Fair, a long-term loon biologist who has written extensively about Yellow-billed Loons and who has studied loons (and other wildlife) across North America. Jeff's enthusiasm for loons, and his deep caring for the places they live, is immediately evident. Two and a half hours later, I felt I had left my Pacific Flyway bias behind, but what I learned raised an endless list of other questions.

As with other species whose migration story has more accurately unfolded with the use of satellite telemetry (see Bar-tailed Godwits Face Conservation Challenges), the Yellow-billed Loon's movements have been demystified a bit over the past two decades. Jeff shared information from telemetry studies: from 2002-2019, a total of 92 Yellow-billed Loons were fitted with satellite transmitters to better understand their distribution, summer and year-round movements and survival across seasons. Researchers studied four populations of Yellow-billed Loons that breed in the U.S. and Canada.

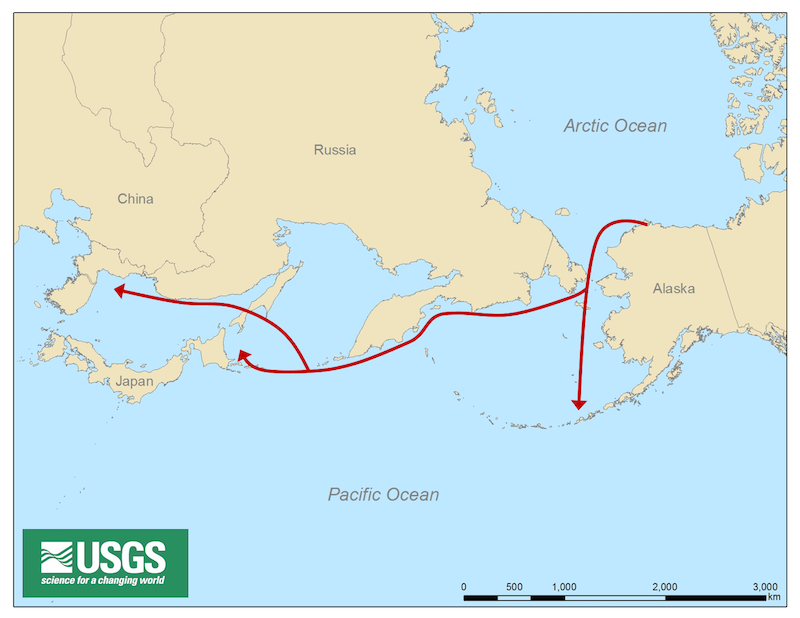

One of those four populations breeds along the Arctic Coastal Plain (ACP) of northern Alaska (and never goes near the Pacific Northwest). The red lines on the map below show the general migration pathway after loons were fitted with transmitters at their breeding areas on the ACP. Most of the birds head to Asia in September, except the occasional rebels who turn south to the Aleutians.

Map source: Ecology of Loons in a Changing Arctic (linked below)

The breeders from another population – that found in Canada's Western Arctic – migrate to wintering areas throughout the Kodiak Archipelago and Aleutian Islands. Many of the birds that breed on Alaska's Seward Peninsula, a third population, also favor the Alaska Peninsula and Aleutian Islands during the winter months, though some migrate to Asia.

A fourth population breeds on lakes in interior Canada. In the fall, most of them head south to winter along the Pacific Northwest coast of the U.S. and Canada – these are the wintering birds that are depicted on range maps that only cover North America. Except for some of them, Jeff tells me, that turn north instead. These interior "Canada" birds then broadly circumnavigate the coast of Alaska and end up along the Kodiak Archipelago for the winter. The story of migration was certainly a bit more than I had anticipated!

To conserve, we need to understand the threats

When it comes to the conservation of the Yellow-billed Loon, the migratory route matters – as does their selection of breeding and wintering areas. Satellite telemetry can yield information not only about migration, but also about movements and territories during the breeding season. There are only an estimated 3,000-4,000 Yellow-billed Loons breeding in Alaska. The majority of those are found within the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska (NPRA) where expanded, and controversial, oil and gas leasing is proposed. In addition, the landscape on the entire Arctic Coastal Plain is experiencing rapid climate related landscape change. The Yellow-billed Loons need larger and deeper lakes compared to other loon species. Even if the larger lakes persist in a warming Arctic, hydrologic changes may cause disruptions in drainage patterns and fish availability. For a species that has a low reproductive rate, rapid environmental change may pose serious threats.

On a global scale, the threats to the non-breeding birds differ by area, but are significant. Research has shown, for example, that at least some of the loons that winter in eastern Asia – including the Yellow Sea with its known high contaminant levels – have elevated mercury levels.

For Yellow-billed Loons, conservation and stewardship is certainly a complicated picture. And I haven't even brought up the ones that breed in Arctic Russia, where even less is known about the species.